Your Stupid Town

2012-04-09Epigram the 1st:

“Have you noticed how their stuff is s— and your s— is stuff?”

–George Carlin

Epigram the 2nd:

“Do me like the woman from my town would.”

–Drake

I traveled to Portland a couple years ago to spend a long weekend with a friend. Portland, if you’re unfamiliar, is like if NPR built a city, which is exactly as wonderful and horrifying as it sounds. We didn’t attend a Blazers game while we were there—I had just paid to fly 2,100 miles; NBA tickets weren’t happening—but Blazers paraphernalia is something you can’t miss in Portland. Or at least I couldn’t. As an NBA junkie, I’m sort of preconditioned to spot Blazers flags in bar windows, but I suppose you could miss such signage while spending hours in the city block-sized Powell’s Books, grabbing a food cart burrito downtown, or while resisting the urge to propose to a pretty twentysomething in a sundress. (You’re a very attractive city, Portland.) But one of the most interesting things about the city of Portland, at least to me, are the pockets of direly committed Blazers fans scattered across the city like so many snowy clumps of powdered sugar on a piece of artisan french toast. (You do breakfast correctly, Portland.)

Being a fan of a sports team is an identity marker for a lot of people—note how many Facebook and Twitter profiles mention a person’s allegiance to a specific team—but in Portland, being a Blazers fan is an especially unique identity marker because A.) Portland isn’t a sports town in the vein of Boston or St. Louis or Cleveland and B.) Portland doesn’t have a professional baseball, football, or hockey team. (Here I note the existence and rabid fanbase of the Portland Timbers, but being an American soccer fan is an identity marker all its own.)

Being a Blazers fan is, I think, being both a part of the city and apart from the city. It’s like being a fan of Z-Ro, but not Jay-Z. Sure, a lot of people like Z-Ro—they compose a not-insignificant portion of the rap nerd landscape—but it’s not like you could fill Madison Square Garden ten times over with Z-Ro fans. To be a Z-Ro or Blazers acolyte is to be part of a sizable subculture. Blazers fans are a proud subculture. They rep Portland as adamantly as anyone. Their identity is held in being both a minority within their city’s larger culture and an advocate of it.

I’m speaking in broad strokes, and, of course, cities aren’t monoliths. In fact, their unmonolithicness is sort of the point of them, but for the purposes of not having to describe the idiosyncrasies of every person within their borders, we try to define them with a handful of descriptors. We peg towns with an identity. Think Pittsburgh and industry, Los Angeles and Hollywood, Miami and strip clubs. There are filmmakers in Pittsburgh, blue collar workers in Los Angeles, and strippers everywhere, but we assign certain traits to cities because it’s convenient shorthand and not altogether false. It’s not like Pittsburgh is Mecca for avant-garde visual artists, and we’ve just been lying about it for decades.

I have lived in Chicago, a parochial city in its own right, for the past four years. Despite being a city with manifold cuisine, a theater district. a phenomenal downtown, myriad diverse neighborhoods—a rich cultural identity, is what I mean—some of its residents—natives, mostly; Chicago is kind of a midwestern LA in that it houses a lot of transplants—have a strange inferiority complex toward the coasts. They bristle at the mention of New York or Boston or Los Angeles. No city shall be as great as the one that invented the pickle-adornèd hot dog! It’s weird. Because Chicago’s an immense, sometimes beguiling city. I sometimes wonder why its residents—its advocates, really—can’t be satisfied with being a wonderful town in the middle of the country.

Because there exists no objectively great city or town. Where you live is a matter of fit, and where you’re from is a matter of what city your mother was in when her water broke. It’s sort of an arranged marriage: it will affect you, but you don’t have to develop affection for it. I’m from a smallish city in upstate New York, and I kind of hate where I’m from. It’s too small for my liking (both in terms of population and worldview) and most of its citizens would build a giant metal dome over the town if they could. They deserve to suffocate beneath a physical manifestation of their own insularity. Most of them, anyway.

I’m a Cleveland Cavaliers fan because of this town. There were no local sports teams, so I decided to root for my cousin’s favorite team. So here I am: a Cavs fan, but not a Clevelander. I’m trying to figure out whether or not this is important. Ostensibly, it’s not. I’m about as devoted to the Cavaliers as any fan of the team, and I’ve been to Cleveland a handful of times. If I had grown up on the shores of Lake Erie, I don’t think I would be extolling Cleveland’s virtues to non-residents at parties. I’m also just not wired that way. Some people like to define themselves by the groups they are a part of—fanbases, cities, country clubs—but I’m not one of them. One of my favorite things about living in a colossal city is the anonymity it affords me. I can go days without being recognized on the street by a friend or acquaintance. I can just a be a dude on the corner, waiting for the light to change; that recession into nothingness is comforting to me.

But this strong city-team-self triangle—I’m from Cleveland, I love my hometown, and I’m a huge Cavaliers fan—is a crucial part of fanhood for some people. It’s not something that can be easily dismissed. I’m trying to understand it from the outside. Cities—though they’re really just a mass of flesh, concrete, and steel—breathe. They are frighteningly organism-like. And what better way to celebrate that almost-organism than by watching your favorite sports team— ambassadors of your favorite city—assert their dominance over another city’s athletic ambassadors while in the company of fellow residents of your beloved metropolis. You can do this in places all over the country: they’re called sports bars and arenas.

The point at which this native-sports-fan-as-identity-marker thing becomes problematic is when people indulge in the fallacy that to truly understand their passion, you have to be from Sports Town X. I have heard some misguided Clevelanders engage in this nonsense. Which: I get it. People like exclusivity when they’re on the right side of the velvet rope. Clevelanders are almost never on the right side of the velvet rope. Their city is economically depressed; their sports teams have a history of futility; and they’re often on the wrong end of hacky jokes from Sportscenter anchors. My friend from Alliance once deadpanned “Surely, there is nothing worse than being from Cleveland.” What can you say to someone who condescends to you? You don’t understand. You’re not from here. Erect the ol’ giant metal dome over the Mistake by the Lake and embrace your antipathy for outsiders.

I’m not saying most Cleveland Cavaliers fans are like that. Nor are most Bobcats, Blazers, Thunder, Kings, T’Wolves, Grizzlies, or Pacers fans. But those angry, defensive thoughts happen; I’m perplexed by the people who think them. From what I can tell, one of the aspects of The Decision that most angered Clevelanders was the perception that LeBron had turned his back on Northeast Ohio. In deciding to play in Miami, he had not only abandoned the Cavs, but he had yanked his roots from Cleveland’s soil. He would rather live in South Beach, nestled against the bosom of a glitter-pocked stripper! absolutely no one thought after watching The Decision. But you see my point. Clevelanders didn’t just lose a great player: a native son spurned them. We can find the inverse of that sentiment in columns about the extension Russell Westbrook signed this winter with the Thunder. Sure, Sam Presti wanted to lock down one of the best young players in the league, but mentioned in almost every story about the signing: Russell Westbrook actually likes playing in Oklahoma City. The implication is that a player preferring to play in a small market is rare, which it is.

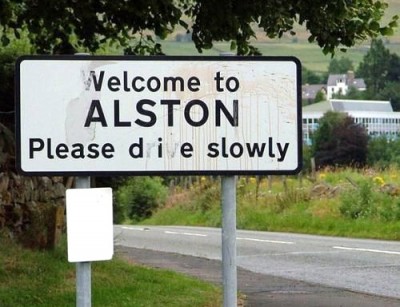

In a season that’s all over except for the crying and the Anthony Davis-related prayers, Cavaliers fans are tempted to look toward free agency, which I know will invoke some sore feelings from Clevelanders. Why should the Cavs have to overpay to lure free agents to their city? It’s where they live, after all; they like it. Regardless, all money being equal, O.J. Mayo would rather play in LA than Cleveland. As someone who moved from small town upstate New York to Chicago, I empathize, and if you don’t understand here’s a tautology: if more people wanted to live in Cleveland, more people would live in Cleveland. More people prefer Chicago, Boston, Phoenix, Dallas, etc. Why would NBA players be any different? There is the odd Russell Westbrook type, but most NBA players would prefer a swank apartment in SoHo to a McMansion on the outskirts of Sacramento. They don’t hate your stupid town. They just found one they like better. It’s got killer Indian food, and they can live near the ocean. Around such criteria do people make a stupid town a home.

I was raised in a small town about an hour north of Dayton and now live in Columbus. As a child, I also was a fan of players (both NFL and NBA; I loathe baseball) more than I was of teams, and I certainly didn’t inherit my allegiance to Cleveland sports from my family. Proximity might suggest I become a Bengals fan, but I loathe the franchise and I tell myself that it is mostly due to Mike Brown. Both sides of my family were raised just south of Toledo. My paternal side of the family is more a fan… Read more »

As a service member living over in Germany for 12 years, it was hard to see anything on the Armed Forces Network worth watching except for when the Indians were in the playoffs, the Cavs were in the playoffs and the Browns were in the wild card vs Pittsburgh. They claim to show everything and every team, however, the big market teams get the lions share of the air time. I can sympathize with every Ohioan and Clevelander about the misery that is our franchise(s) riddled past, but we wallow so much in the past that we do little to… Read more »

Cooley – lol you just made my day.

Agreed…I am a Cleveland fan through my parents, and have never even been to the city personally. Nonetheless, I probably spend more time thinking about the Cavs than about anything else, and will be up until 3AM working tonight because I want to watch them play a meaningless game against the Bobcats for two and a half hours. And whether they win or lose, I will remain emotionally conflicted over the matter for the rest of the night. So it goes.

I’m talking about the later part where it gets into debates about Obama, Goldschmidt, and Koch-funded swipes at light rail. The first part absolutely ties in. Maybe I’m just really sensitive about light rail…

Was it nsfw or something? I thought it tied into what Colin said about NPR designingPortland

Tom, that article ends up skewing into divisive, partisan politics. Try to be more careful with the links. On the other hand, I do think that some people from outside NE Ohio proper ‘don’t get it.’ It’s really hard to put a finger on why, but I’d guess that it relates to having the “heartbreak montage” played whenever we get close, but still inevitably fail. There’s just this overwhelming sense of bitter pessimism that’s been ground into Cleveland fans from a very young age. I mean, the Indians built Jim Thome a statue, and what he did is, to some… Read more »

Colin – I love your writing and the passion of this blog more generally. So I don’t mean anything personal, but I have to disagree with you. Being from Cleveland does matter. And its not in a “velvet rope,” “we’re insiders” sort of way. It has to do with understanding the culture of the city, and how closely linked it is to the culture of our sports team. As Ben described well, Cleveland is a beat up place, and the failures of our sports teams have coincided with the economic struggles of our city. For me, my sports loyalty to… Read more »

Portland has more strip clubs per capita than any city in America – so Miami needs a new “thing”. Also, Portland is the greatest city ever to visit – it’s literally a people circus and the animals don’t bite. But as Colin so eloquently put it – there is a horrifying aspect to Portland. http://www.weeklystandard.com/print/articles/insufferable-portland_631919.html That triangle you spoke of – to say it is important to some fans and that “It’s not something that can be easily dismissed” is an understatement. The driving force that creates the sports environment we live in is BUILT and SUSTAINED by these city-team-self… Read more »

While I don’t doubt someone can be a great, dedicated fan without having grown up in a town, I still agree with those who say “you don’t get it.” There is a lineage of being a Cleveland fan/Clevelander that is relevant. Like the city, Cleveland sports WERE dominant and it was the subsequent decline and all too frequent heartbreaks that so closely resemble the city’s history. The economic boom of the late 90’s and its correlation with the brief hope with the Indians is not a small deal. There have been numerous studies on the economic impact of a championship… Read more »

I’m a Cavs fan, but live nowhere near Cleveland. I started following them when I went to the University of Akron, and really grew to like them a lot, but there were times when I felt like an outsider among some of my more hardcore friends since I’m not a Tribe or Browns fan and only followed the Cavs since like 2003. I grew up near Toledo, so if I were to have picked a local team as a youngster I would more likely be a Pistons fan (but I only liked players as a kid, and didn’t care for… Read more »

If you’re not from Cleveland and you choose to be a Cleveland fan, that’s cool (maybe you have even more cred. You weren’t born into it and yet you choose the joys of Cleveland fandom). If you’re not a cavs fan at all (let’s say you’re a warriors fan to choose a totally random team) but you pretend to like the cavs to further your writing career that’s not as cool.

/Has no idea who Z-Ro is

@Dano – I think the only reason I ever find myself wanting children (I am still pretty young) is for exactly that. I was born in Cleveland, but I spent most of my formative years in Texas and North Carolina, along with College in Florida. But my Dad, and by extension my brothers and I were always “from Cleveland.” The Browns, Cavs and Tribe were a big part of our relationship, and I think that’s great. Fandom has a special way of being sorta hereditary. And Colin, we’re glad to have you!

I think we can land Eddy Curry if we just give him a tour of Melt and finish the meeting with a Parmageddon.

Another excellent article. I’ll say this again: Clevelanders are not upset that LeBron left Cleveland. They are upset about HOW HE DID IT. No one in Cleveland blames anyone for leaving Cleveland. It happens every day*. LeBron just happened to do it in front of the world, saying, “I’m taking my talents to South Beach.” I mean, really? Cleveland has a long, well-documented history of heartbreak. So when LeBron joined the ranks of those breaking the city’s collective heart, you could almost sense the city pleading, “How could you?” This used to upset me most, until I realized that LeBron… Read more »

I haven’t looked at this summer’s free agents much lately. I’m starting to lean towards the Cavs trying to sign a veteran, established starter type. I’m over the team being horrible, plus if the contract is three years, the player is off the books before Kyrie’s extension comes up. If the Cavs offer more money over three years than anyone else offers for four, and the player still chooses to go elsewhere, that will be frustrating. Is there really Indian food that good in other places?