Thank You, Whoever You Are

2012-05-03Antawn Jamison announced about a week ago that he will not be returning to the Cavaliers next season. I met this news by glancing out the window at a crow perched on a telephone wire. Then I walked to the fridge and made myself a roast beef sandwich. It’s unremarkable that a guy who will turn 36 in the offseason would rather play for a title contender than a team in year three of a rebuild that will extend beyond his career. Like, it’s literally unremarkable; it need not be remarked upon. Cars are useful. Water slides are fun. Antawn Jamison is old and would like to win a championship.

Jamison’s departure brings a formal close to an era, of sorts—a musty crawl space of time that bridges the end of LeBron James’s Cavalier tenure and the beginning of Kyrie Irving’s. He was the last player Danny Ferry acquired before Ferry and the Cavs parted company in June of 2010, and, in a lot of ways, Jamison was emblematic of Ferry’s ill-fated attempts at surrounding LeBron with sufficient talent. News of the Antawn Jamison trade was met with mild approval. He was the type of good-not-great, not-quite-worthy-of-being-LeBron’s-wingman player with which Cavs fans were very familiar. For his first week as a Cavalier, his name might as well have been Not Amar’e Stoudemire. (In some alternate universe, Amar’e for J.J. Hickson and a dumpster’s worth of draft picks was a real thing, the LBJ-Amar’e Cavs won a championship, and Scott Sargent happily changed the name of Waiting for Next Year to This Is a Blog About Cleveland Sports Teams.)

Jamison averaged 15-and-7 in the 2010 playoffs, though he was markedly better against the Bulls than the Celtics, and Cavs fans will remember Kevin Garnett devoured him in the Eastern Conference Semifinals. If LBJ hadn’t performed like a robot who had just fallen into a dunk tank an hour before tip-off in Game 5, Jamison might have suffered the same scrutiny Mo Williams faced after he seemingly missed every important open three against Orlando in 2009.

Then LeBron left, Mo Williams’s wounded soul was sent to Los Angeles, and Jamison became the best scorer on the worst team in the league. A year later he was the second-best offensive player on a team that was still really bad. As is his wont, he handled this predicament like a gentleman. Antawn Jamison—who has had a great career, mind you; we’re talking about a two-time All-Star—is defined by this gentlemanliness. He is difficult to discuss in any detail mostly because all we know about him is what we see on the court and his impenetrable good guy-ness. Have you heard an announcer mention Antawn Jamison without citing a.) his professionalism or b.) his arsenal of strange scoop shots and floaters?

I, too, have trouble escaping either of these things. I’m convinced, when his UNC team was getting blown out by Utah early in the second half of the national semifinal in the 1998 Final Four, that I saw Jamison, behind the play and out of frustration, briefly put a Utah player in a headlock, but I was eight at the time, and being eight is like waking up every day and ingesting a bag of hallucinogens. I would love to ask him if that’s a thing that actually happened if we ever ran into one another. Mostly because it’s the only remotely dishonorable thing I’ve ever maybe seen him do. But we will never cross paths, Antawn Jamison and I. If he showed up in my living room, I would feel like Adam the moment he ate from the Tree of Knowledge and realized he was not clothed—an intense, searing shame. I’m morally naked, Antawn. Please don’t look me in the eye.

What can you say about Antawn Jamsion without sounding condescending or reductive? He is a person, after all. Imperfect, with indentations in his character. (Though I wonder if those indentations are perfect and symmetrical, like on a golf ball.) His blood surely isn’t the shade of taupe I imagine it to be.

Perhaps he is best conceived of as a man with aluminum skin. And I don’t mean that pejoratively—there’s perhaps teeming humanity beneath that reflective surface, but we lack access to what’s underneath. All we—as fans, writers, whomever—can do is shout interrogative statements at Jamison’s exterior. And we receive in return nothing but ghost-mouthed iterations of our own words. A lot of athletes are like this to some degree—if you hate an athlete who hasn’t sexually assaulted or murdered anyone, it really says more about you than the athlete—but Antawn Jamison’s skin is as unfissured as anyone’s. Questions lobbed at him ricochet back toward our more penetrable hides. Maybe we learn something about ourselves. We learn almost nothing about Antawn Jamison. We should thank him, then, for his patience. It must be exhausting to be a mirror: everyone talks about themselves while they peer into you.

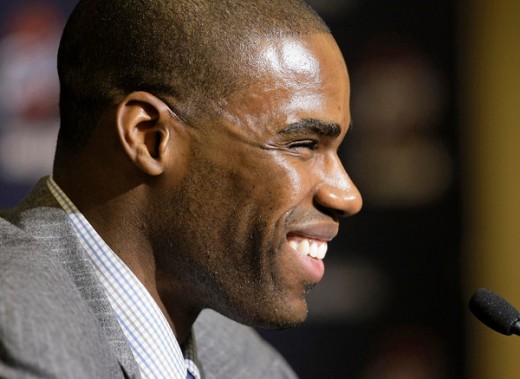

It would be disingenuous of me to say I don’t know anything about Antawn Jamison. I know he has emerged from this melting scrap heap of a Cavalier team still remarkably handsome, with a piercing smile that I hope to see more of when he plays in Dallas or Miami or wherever next year. I know he will bring his class, his articulate way, his still-decent jump shot to whatever future home he inhabits. I know he deserves the future success he encounters. May he have an excess of it. Farewell, Antawn.

“One Night and one more time, Thanks for the memories, Even though thety weren’t so great”

But in all honesty I kind of will miss Jamison.

Great read, Colin.

“being eight is like waking up every day and ingesting a bag of hallucinogens”.

That receives my vote for line of the year. Classic.

Colin,

If you can acquire a copy of an article by Jim Murray, written a long time ago, that describes the sportswriter’s detached retina, then you will have in your hands the greatest sportswriter-generated article I have read.

You, like Jim Murray, have a gift for making ordinary things seem extraordinary.

Great article.

Thanks for contributing great public articles like this. You’re letting a lot of fans share their voice vicariously through your eloquence in making these blog posts.

Really good piece. I doubt many other NBA blogs have these types of articles.

This was THE best sports article I’ve ever read. Keep up up the good work.

Impeccably accurate analysis.

If there were such a thing as a person that follows individual Cavs player details needing a talented and funny wordsmith, you my friend, would be on to the next gig.