The Argument Index

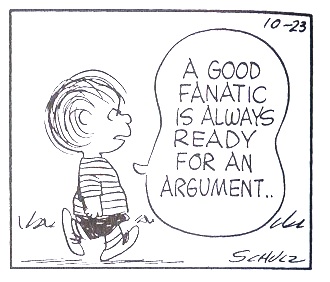

2012-12-25The never-ending quest to be right about sports has always been boring and ineffectual. I suppose the helplessness of fandom drives some of us to importunate, blustery denial—practiced by the types who hop on a sports talk radio call-in show and lecture an athlete who almost certainly isn’t listening about how if he doesn’t pick up the defensive intensity, he’s going to be run out of town, as if the bloviating caller had the power to make such decisions. If you’re reading this blog, you’re likely enough of a basketball obsessive to have frequented or at least perused some forums where a loud simpleton insists two games into the season—misspelling words all over the place, natch—that the coach has to be fired because he has lost the locker room or the new offense that he has installed will never work. You get it: needlessly angry irrationality is pervasive in sports. If you don’t, imagine a mustachioed, slightly overweight security guard shouting at some skateboarding children or that same mustachioed, slightly overweight security guard incensed that Hardee’s has discontinued the Sludgeburger®. Replace his words about skateboards and deep-fried whale liver with sports words like “hustle” and “the will to win.”

We would all like to fancy ourselves better than my pudgy security guard straw man, but some of us are not, and some of us are on TV shows and have sports columns in major markets, and unfortunately, we can sketch a venn diagram in which we discover that people who possess my pudgy security guard straw man’s impotent rage and people who possess a forum that reaches millions of sports fans are—*defeated guffaw*—sometimes the same people. Skip Bayless is their sunbaked king, but there are others—writers and pundits who disingenuously or otherwise tell it like it is because they are not afraid to make bold declarations and speak truth to, I dunno, power? As if there were truth in sports, as if there were power.

I blame this major media reductive content machine—time-killing Sportscenter debates about “Who’s better? Player X v. Player Y;” Bleacher Report listicles; overrated/underrated discussions; power polls; conversations about “clutch;” Skip Bayless, et al.—for running rigid debate topics into the ground for so long that the analytics community got pissed off enough to say, “Y0! Here’s a statistical breakdown of Kobe’s late-game performance. It’s not great. Please be quiet.” The mistake the analytics men and women made was in thinking they could end facile debates or that the mainstream would listen to them. Incorrigible sportswriters and talking heads stage these debates because they rile up reader- and viewership and because they’re easy to argue—you don’t have to do much work to get a reaction out of people if you say that Russell Westbrook is the reason the Thunder will never win a title; the topic is already charged and all you have to do is make the assertion and say some vaguely insulting stuff about how Westbrook doesn’t “have what it takes” or whatever. I doubt many sports columnists and talking heads are excited to argue about Extremely Tired Debate Topic X or even if they particularly care. They just don’t want to think too hard. It’s how you end up with Rob Parker calling Robert Griffin III a “cornball brother.” Race is a pre-charged topic; it just happens to be one that matters enough in the real world to get Parker suspended for saying something stupid about it.

Analytics-driven writers—unlike a lot of the pundits you see and hear on major networks—are generally thoughtful people who try to help their reader- and viewership better understand the game. I learned a lot of what I know about how NBA offenses work through Sebastian Pruiti’s now-defunct NBA Playbook, and John Hollinger’s PER Diem column helped me understand how various advanced stats function and what they tell us about what we’re seeing on the floor. Kirk Goldsberry’s maps over at Grantland are informative and pretty. Hell, this blog exists on a network that swarms the Sloan Conference each year and possesses a lot of writers who use advanced stats and analytics in their articles. I actually feel a bit out of place as a writer who compares crossovers to butterflies for a network that’s often so analytics-obsessed, but I see the value in the movement.

I think because the analytics community usually writes smarter and more engaging articles than your average sports talk radio bully or snide newspaper dinosaur, we tend to think of the two groups as occupying different spheres, but they overlap more than you would expect. This is in part because the mainstream sports conversation is so inane that it provides an easy target for the analytics community. In the same way T.J. Simers writes some trollgarbage essay about Pau Gasol being “soft” because it’s easy, it’s similarly easy for an analytics person to take apart that assertion with a few handy YouTube clips and some snark. Writers are just content farmers sometimes; we can’t always mine the universe’s profundities. Sometimes we just bang out mildly entertaining or informative content for the sake of filling space while we try to figure out how to say something more interesting the next time we publish.

But righteousness and clowning troglodytes is addictive, and this ostensibly symbiotic relationship between mainstream sports writers’ and pundits’ idiocy and analytics-driven writing has had a poisonous effect on the latter. Or maybe it’s just that people—even or maybe especially smart ones—like to feel superior about things. At any rate, I feel like a lot of analytics-based writing has lapsed into the same sort of “let me tell you the truth about sports, dummy” tone common to an imperious talking head. You can see it in every second-guessing article about what a team should have done at the end of a close game and every derisive comment about hero ball. More and more, the exuberant “let’s learn about basketball together” tone is being replaced by one that sounds paternalistic and patronizing.

The tone shift is understandable. When you’re armed with knowledge, you feel empowered and can easily come off a whit hubristic. We’ve all been overexcited about something we’ve learned at one point or another and relayed that information to a friend like we were Prometheus bringing fire to humankind. But as I wrote at the beginning of this season, we’re all hacks to some degree. We’re all looking at this game through prisms, and analytics is one prism. If you’re working for an NBA front office, then having the best predictive models and being right about things more often than not is is important; it gives you a competitive advantage. But outside of that context, you’re a carnival weight-guesser or a weatherman. Yet still, some analytics writers carry themselves like they hold a secret truth in their back pocket that they occasionally deign to share portions of with the public. They’re the Gnostics of the NBA landscape.

I like the analytics community and because I like them, I suggest this: stop worrying about and comparing yourself to idiots. Will Leitch wrote this past summer that perhaps, if we stop acknowledging Skip Bayless, he’ll go away. I don’t know if that’s true, but I know those of Bayless’s ilk are not worth our time; loud, angry message boarders are not worth our time; trying to prove to the world how smart we are is not worth our time. All writers should write like their audience is intelligent and thoughtful and be respectful of that assumed intelligence and thoughtfulness. No one is an arbiter of truth here.

All of this isn’t to tell you what to argue about or whether to argue at all. The inspiration for this piece was actually a fraught discussion with fellow C:TB staffer Tom Pestak about Tristan Thompson, the Cavalier bench, and Byron Scott. We were both blowing off steam—Tom about his problems with Scott’s aloofness, and me about my anxiety over the team’s future. If any of it were particularly enlightening, I would reprint it here. Let the lack of quotation marks speak volumes.

I know that I’m more self-hating about my tendency to lapse into stereotypical bar room arguments than other fans, and I know plenty of reasonable people who like sports because it’s an opportunity to have good-natured arguments about a topic in which they are invested. But I’m bored with some of it. I’m sick of listening to and reading myself and others trying to figure out if the Kyrie Era Cavaliers can be good because it’s a pointless endeavor. If the young players develop and the front office makes a few choice moves over the next couple of years, the team will be good. If some of those things don’t happen, the team will be less good. And the tenor of the conversations about the prospect of this good-/less-goodness leaves me cold—people virulently professing that the team definitely is or definitely is not headed in the right direction. Does your ill-gotten certainty comfort you? I’m confused.

Anyway, pay attention to statistics and video analysis; pay attention to draft prospects; pay attention to Kyrie Irving’s defense; pay attention to Byron Scott’s substitution patterns; pay attention to anything that interests you. Just keep in mind that each of us follow sports because they provide us with some sort of ineffable sensation we cannot experience outside of sports. We follow sports because they are important to us but they are not important in any objective sense. That we can care so deeply about something that’s not actually important is amazing and freeing. I think constantly about death and failure and addiction and things that can actually ruin me; to vex over Tristan Thompson’s development for 1500 words is therapeutic.

Rap crit luminary Andrew Nosnitsky tweeted out a month ago, in response to a deluge of attacks from Kendrick Lamar fans about the “classicness” (ugh) of his new album, in fittingly exasperated all caps that “NOT EVERYTHING YOU READ IS AN ARGUMENT SOME PEOPLE JUST LIKE TO THINK ABOUT STUFF BECAUSE THINKING CAN BE FUN TOO.” This is all we’re ever really doing about art and about sports (which is not unlike art): thinking about stuff and kicking around ideas. Statistical breakdowns, think pieces, video analysis, etc.: it’s all just talk and sometimes that talk is convincing or beautiful or insightful or whatever. But it’s all about what you want to talk about and how you want to talk about it. We can treat sports as this weird, prismatic, humbling thing that’s a cross between a detective novel, a Rothko painting, and a gladiatorial competition, or we traffic in polemics. It’s a decision we make when we write an article or comment on a blog post or record a podcast, and it’s ultimately an arbitrary decision, but I find one outlook a great deal more interesting than the other.

The theory of existentialism in sports writing… nice. I very much enjoyed the article. As for analytics based content versus passion based content, I have found the analytics to be a good tool for finding observational bias. There’s no more polarizing figure when it comes to statheads versus mustached security guards than Kobe Bryant. Kobe is an infuriating player who takes a litany of bad shots, and has an reputation that some feel is overrated for being “clutch. Then Kirk Goldsberry wrote at the beginning of the month about the “Kobe Assist,” which proved some of the observational bias of… Read more »

I’m sorry but the gist of the argument here is it “just doesn’t matter,” right? Is this supposed to be insightful? I trust the author is in his 20’s where these types of realizations are a vital, if tedious, part of “growing up.” It however could also be seen as a cop-out. Something I note with the majority of the writers here. They can snark and get indignant with the best of them then retreat behind the wall of “it just doesn’t matter” when the pushback becomes to furious. Finally, Colin, if you’re so “bored with it” then stop writing.… Read more »

This is a very good post. Thanks Colin. Given that this subject has been raised, I think its important to note that this blog (imo) has shifted to a more righteous tone in the last couple years. Specifically, many of the posts take extreme positions about prospects who haven’t played enough games in the NBA to justify any strong conclusions. I am thinking here of the JV stuff, TT, Waiters, the over-reaction to Cavs getting the 4th pick, etc. In the spirit of Colin’s post above, I hope this blog can move back to a more objective tone, and can… Read more »

Well said Bric. I actually get into “spirited debates” with guys on various sites/message boards all the time regarding this. One guy solely uses +/- as the basis of his argument. Essentially, statistics (standard and advanced) should be used to supplement your knowledge based on watching the game of basketball. They have their place…but no statistic (no matter how “advanced”) tells the whole story. Low assists for a PG? Maybe he’s making passes but his guys aren’t making the wide open shots. Turnovers? Are they actually being credited to the right guy? Is it a miscommunication between the guy throwing… Read more »

“Advanced Statistics” are advocated by analysts who often have no idea of how those stats are compiled.

If you analyze the stats, you can see all kinds of things wrong with them.

That doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be used’ to the contrary, I am all for looking at them.

However, if you know the game, and you know the stat is misleading, then trust your experience.

This article provided solid analysis.

^*Ask was supposed to be And on the last line

And become really rich while we do it.

Like many things in sports I think this conversation of analytical objective people outside the main stream knowing more but alienating themselves because of their assumptions and tone translates to other things. I believe this same problem exist in the world of politics. Somehow this past election wasn’t decided on tight money vs loose money, how to fix the banks education the has code or anything that’s of issue. It somehow became about Equal pay for women? Contaception? and Romney being Rich. If Fox and MSNBC and more importantly the major networks pretended that the nation gave a damn about… Read more »

You make a lot of good points about sports media that is not only limited to sports but is parodied in all areas of interest, politics, religion, science, music etc. I think everyone could take a minute to step back recognize the foolishness of most things we in the first world have the luxery of being invested in and to ask themselves “Am I acting like a know it all?” I know I’m guilty of it just as much as the next guy. Great article.